Listening Guests

2025

Single-channel video, multi-channel (or stereo) sound

38 minutes

Listening Guests begins with the belief that a distinct mode of listening exists shaped by the experiences and histories of diaspora. It explores the complex relationships of diasporic communities form with listening through language, music, and various aural events in daily life. Diasporic senses are closely tied to identities shaped within the shifting dynamics between the homeland, the host country, and the diaspora communities. As these three spheres are in constant flux, diasporic communities negotiate and mediate their positions within changing political and economic contexts and varying degrees of access to cultural resources. In doing so, they cultivate unique listening practices and ethics that reflect the particular spatiotemporality of diasporic life.

To explore this diasporic listening, the work focuses on two communities: the Koryoin (ethnic Koreans from the former Soviet Union) community in Korea, and Korean immigrant community in Los Angeles. The first generation of Koryoin largely migrated to the Russian Far East during the Japanese occupation in search of better prospects, only to be forcibly relocated to Central Asia under Stalin’s regime. The Koryoin living in Korea today are mostly descendants of those who returned in the 1990s, seeking improved economic opportunities, with the majority now being primarily second to fourth-generation immigrants. They partake in cultural content from Korea, Russia, and various other regions. The history of Koreans’ mass immigration to the U.S. began in the early 20th century. The number of Korean laborers migrating to Hawaii as farm workers had drastically increased by 1905, competing with Japanese laborers who had already settled down in the island. After the Korean War in the 1950s, masses of war orphans were adopted to the U.S., and highly degreed Koreans who already resided in the U.S. for study purposes determined not to return to their homeland. The revision of the Immigration Act in 1965 resulted in a precipitous increase in Korean emigration; 22% of Korean immigrants ended up settling in the Los Angeles area as of 2005.

In this work, I examine how their listening practices are shaped through processes of relocation and adjustment, and I investigate the power and potential of sound and listening in forming migrant experiences. The film is structured around questions that explore language acquisition, musical production and consumption, and everyday aural events. These questions emerged from an engagement with “sonic ethnography,” a methodology that foregrounds the role of sound and listening within ethnographic narratives. This approach engages the ethnographic potential of sound by attending to sonic environments and by employing process-oriented modes of sound documentation.

(KR)

2025

Single-channel video, multi-channel (or stereo) sound

38 minutes

Listening Guests begins with the belief that a distinct mode of listening exists shaped by the experiences and histories of diaspora. It explores the complex relationships of diasporic communities form with listening through language, music, and various aural events in daily life. Diasporic senses are closely tied to identities shaped within the shifting dynamics between the homeland, the host country, and the diaspora communities. As these three spheres are in constant flux, diasporic communities negotiate and mediate their positions within changing political and economic contexts and varying degrees of access to cultural resources. In doing so, they cultivate unique listening practices and ethics that reflect the particular spatiotemporality of diasporic life.

To explore this diasporic listening, the work focuses on two communities: the Koryoin (ethnic Koreans from the former Soviet Union) community in Korea, and Korean immigrant community in Los Angeles. The first generation of Koryoin largely migrated to the Russian Far East during the Japanese occupation in search of better prospects, only to be forcibly relocated to Central Asia under Stalin’s regime. The Koryoin living in Korea today are mostly descendants of those who returned in the 1990s, seeking improved economic opportunities, with the majority now being primarily second to fourth-generation immigrants. They partake in cultural content from Korea, Russia, and various other regions. The history of Koreans’ mass immigration to the U.S. began in the early 20th century. The number of Korean laborers migrating to Hawaii as farm workers had drastically increased by 1905, competing with Japanese laborers who had already settled down in the island. After the Korean War in the 1950s, masses of war orphans were adopted to the U.S., and highly degreed Koreans who already resided in the U.S. for study purposes determined not to return to their homeland. The revision of the Immigration Act in 1965 resulted in a precipitous increase in Korean emigration; 22% of Korean immigrants ended up settling in the Los Angeles area as of 2005.

In this work, I examine how their listening practices are shaped through processes of relocation and adjustment, and I investigate the power and potential of sound and listening in forming migrant experiences. The film is structured around questions that explore language acquisition, musical production and consumption, and everyday aural events. These questions emerged from an engagement with “sonic ethnography,” a methodology that foregrounds the role of sound and listening within ethnographic narratives. This approach engages the ethnographic potential of sound by attending to sonic environments and by employing process-oriented modes of sound documentation.

(KR)

#1-2

Exhibition view of Korea Artist Prize (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Seoul, 2025). Image courtesy of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Photo: Chulki Hong.

#3-7

Video still.

Trailer

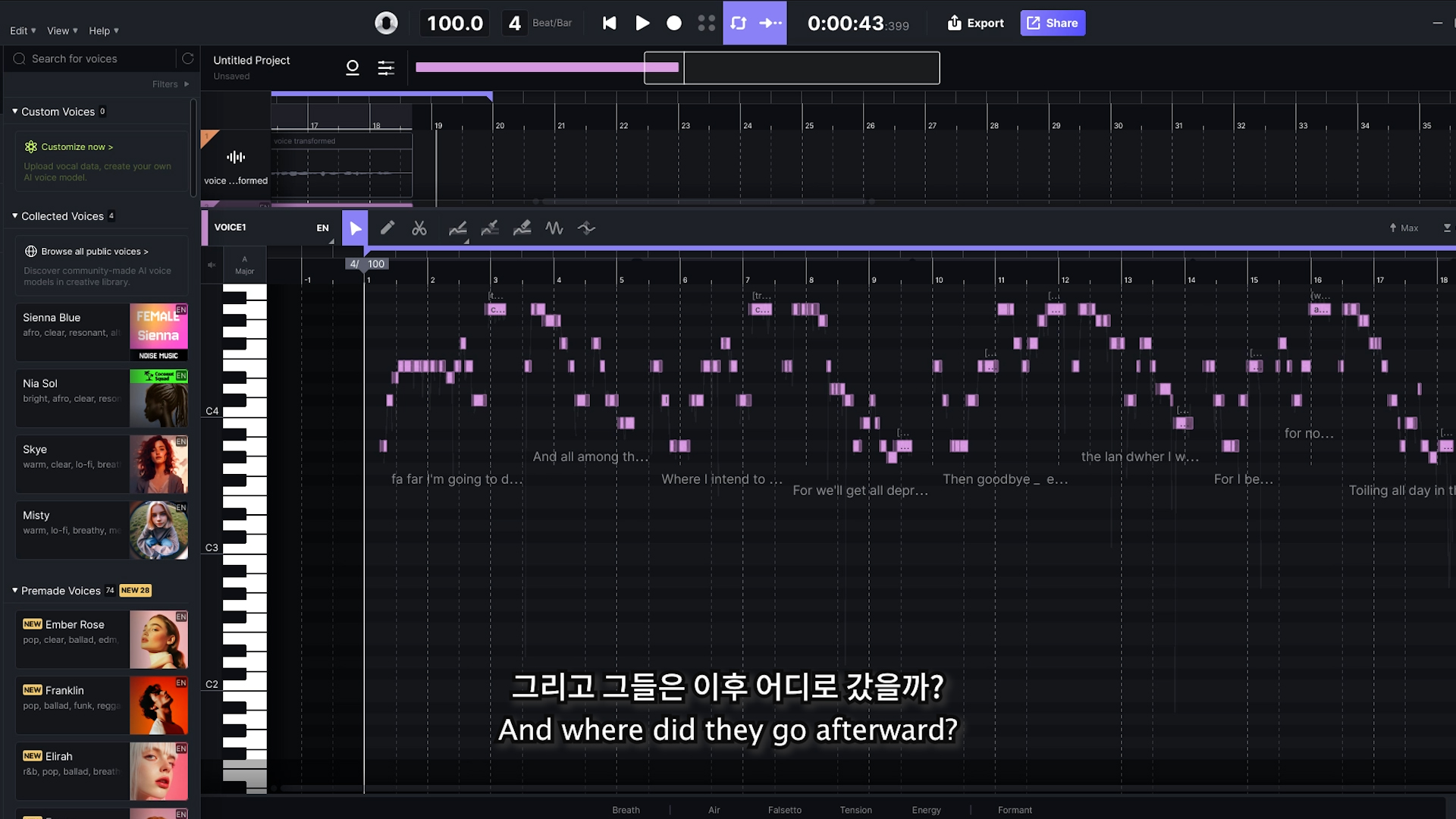

To Future

Listeners Ⅲ

2025

Single-channel video, stereo sound

12 minutes 25 seconds

The song heard in the video is an Irish immigrant song recorded in the United States in the early 20th century. Originally captured on a wax cylinder in an Irish male immigrant's voice, the song is digitally transformed within the work into a choral arrangement sung by women. Most Irish women immigrants, upon arriving in the United States, were dispersed into domestic work. As they became part of the households that constantly required their presence, they found it difficult to form their own communities.

By the 19th century, women made up more than half of the immigrant population. However, historical narratives of immigration have largely been shaped by male voices and memories, leaving the presence of women and their role in shaping discourse overlooked for generations.

This work presents the process of constructing a choral voice of immigrant women—voices that were never formally recorded. It reflects on how these women existed between history and oblivion, resilience and constraint, and resistance and tradition.

(KR)

2025

Single-channel video, stereo sound

12 minutes 25 seconds

The song heard in the video is an Irish immigrant song recorded in the United States in the early 20th century. Originally captured on a wax cylinder in an Irish male immigrant's voice, the song is digitally transformed within the work into a choral arrangement sung by women. Most Irish women immigrants, upon arriving in the United States, were dispersed into domestic work. As they became part of the households that constantly required their presence, they found it difficult to form their own communities.

By the 19th century, women made up more than half of the immigrant population. However, historical narratives of immigration have largely been shaped by male voices and memories, leaving the presence of women and their role in shaping discourse overlooked for generations.

This work presents the process of constructing a choral voice of immigrant women—voices that were never formally recorded. It reflects on how these women existed between history and oblivion, resilience and constraint, and resistance and tradition.

(KR)

#1

Exhibition view of Korea Artist Prize (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Seoul, 2025). Image courtesy of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Photo: Chulki Hong.

#2-4

Video still.

1 min video excerpt

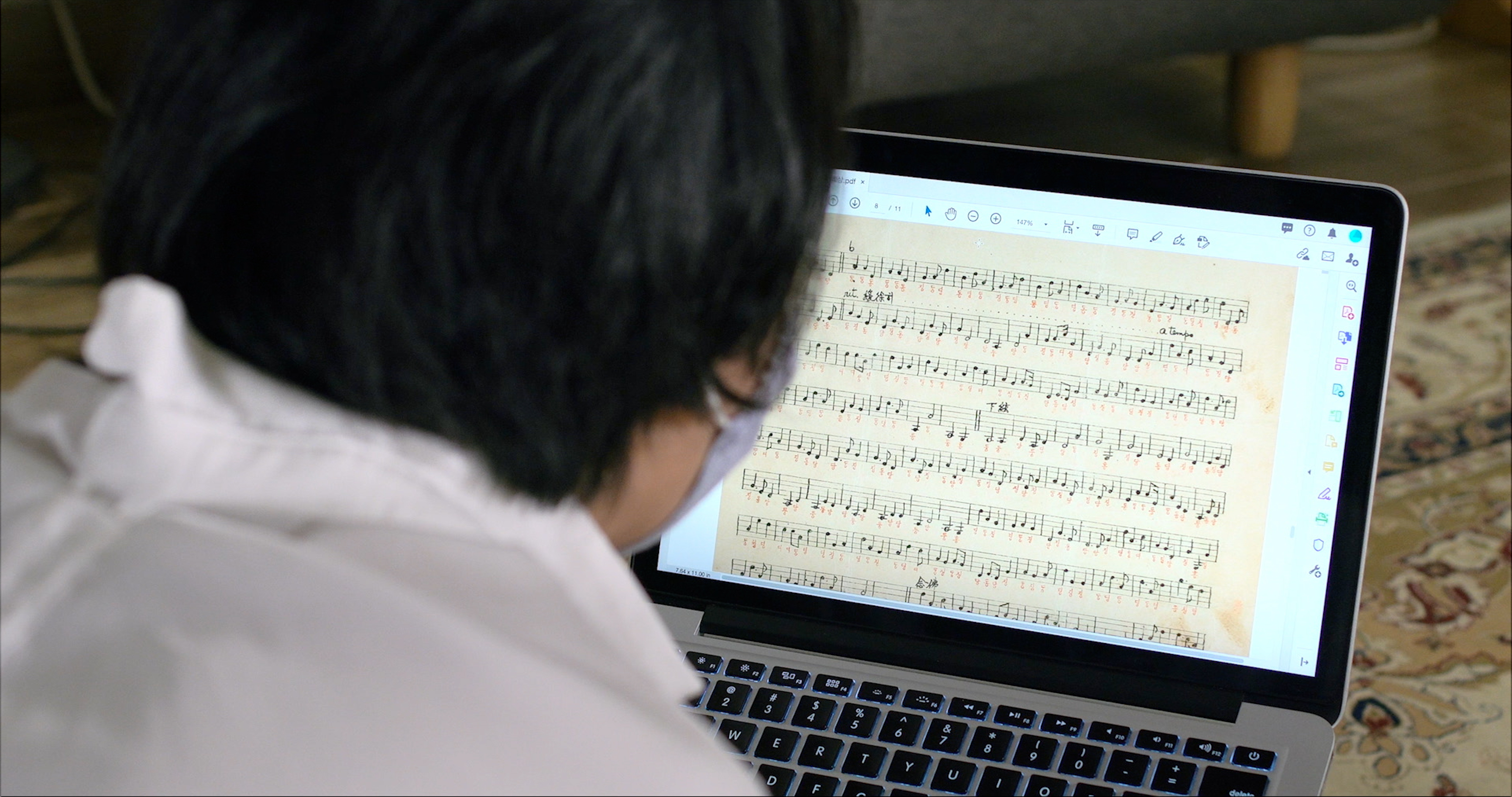

A Story of Oseonbo: Sounds Lost in Translation

2022

Single-channel video, stereo sound

47 minutes 8 seconds

This work examines a musical score created during Korea’s modernization period, a time marked by the influx of foreign cultures and the frequent erosion or transformation of traditional practices.

Joseon Guak Yeongsan Hoesang is a score transcribed in 1914 by Insik Kim, a teacher at the Joseon Court Music Study Institute, who translated the yanggeum (Korean dulcimer) score for the piece Yeongsan Hoesang into Western staff notation. Featuring gueum (a form of oral notation or symbols used in place of musical notes to mimic instrument sounds) written in Korean language, the score is the earliest known example of Korea’s old notations being adapted into the Western notation system by a Korean. Musicians at the time compiled scores on staff notation in an effort to introduce traditional Korean music to the outside world or to incorporate foreign sensibilities into Korean musical compositions. However, at the same time, there were also sounds and techniques in traditional music that could not be adequately conveyed through Western staff notation.

Centered mainly on interviews with traditional music performers, composers, and researchers, the work reconstructs their various speculations on the sounds and sentiments in the score that have been lost or transformed in the process of translation. By combining archival materials and ordinary video footage, the work also investigates the colonial history of music education and contemporary musicians’ ambivalence toward what has remained through this educational legacy. In doing so, it raises questions about the institutionalization of staff notation and other forms of musical systems that have become entrenched as contemporary musical frameworks, while reflecting on today’s traditional music.

Adapted commission by the 15th Gwangju Biennale in 2024

(KR)

2022

Single-channel video, stereo sound

47 minutes 8 seconds

This work examines a musical score created during Korea’s modernization period, a time marked by the influx of foreign cultures and the frequent erosion or transformation of traditional practices.

Joseon Guak Yeongsan Hoesang is a score transcribed in 1914 by Insik Kim, a teacher at the Joseon Court Music Study Institute, who translated the yanggeum (Korean dulcimer) score for the piece Yeongsan Hoesang into Western staff notation. Featuring gueum (a form of oral notation or symbols used in place of musical notes to mimic instrument sounds) written in Korean language, the score is the earliest known example of Korea’s old notations being adapted into the Western notation system by a Korean. Musicians at the time compiled scores on staff notation in an effort to introduce traditional Korean music to the outside world or to incorporate foreign sensibilities into Korean musical compositions. However, at the same time, there were also sounds and techniques in traditional music that could not be adequately conveyed through Western staff notation.

Centered mainly on interviews with traditional music performers, composers, and researchers, the work reconstructs their various speculations on the sounds and sentiments in the score that have been lost or transformed in the process of translation. By combining archival materials and ordinary video footage, the work also investigates the colonial history of music education and contemporary musicians’ ambivalence toward what has remained through this educational legacy. In doing so, it raises questions about the institutionalization of staff notation and other forms of musical systems that have become entrenched as contemporary musical frameworks, while reflecting on today’s traditional music.

Adapted commission by the 15th Gwangju Biennale in 2024

(KR)

#1-2

Exhibition view of PANSORI: A Soundscape of the 21st Century, 15th Gwangju Biennale (Han Hee Won Art Museum, Gwangju, 2024). Image courtesy of Gwangju Biennale Foundation. Photo: Studio Possiblezone.

#3-5

Exhibition view of Frames of Sound (SONGEUN, Seoul, 2022). Photo: Jihyun Jung.

#6-9

Video still.

Trailer

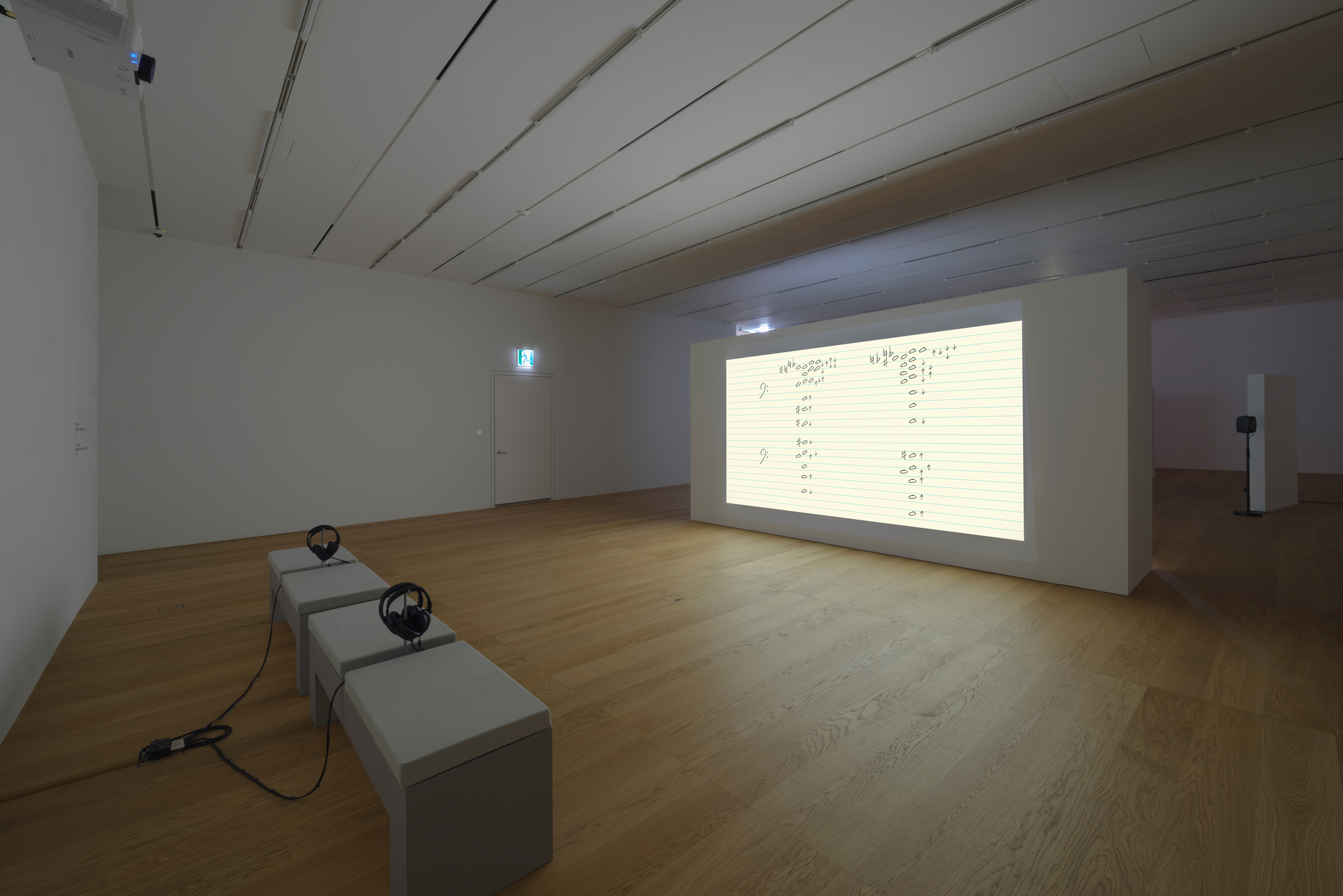

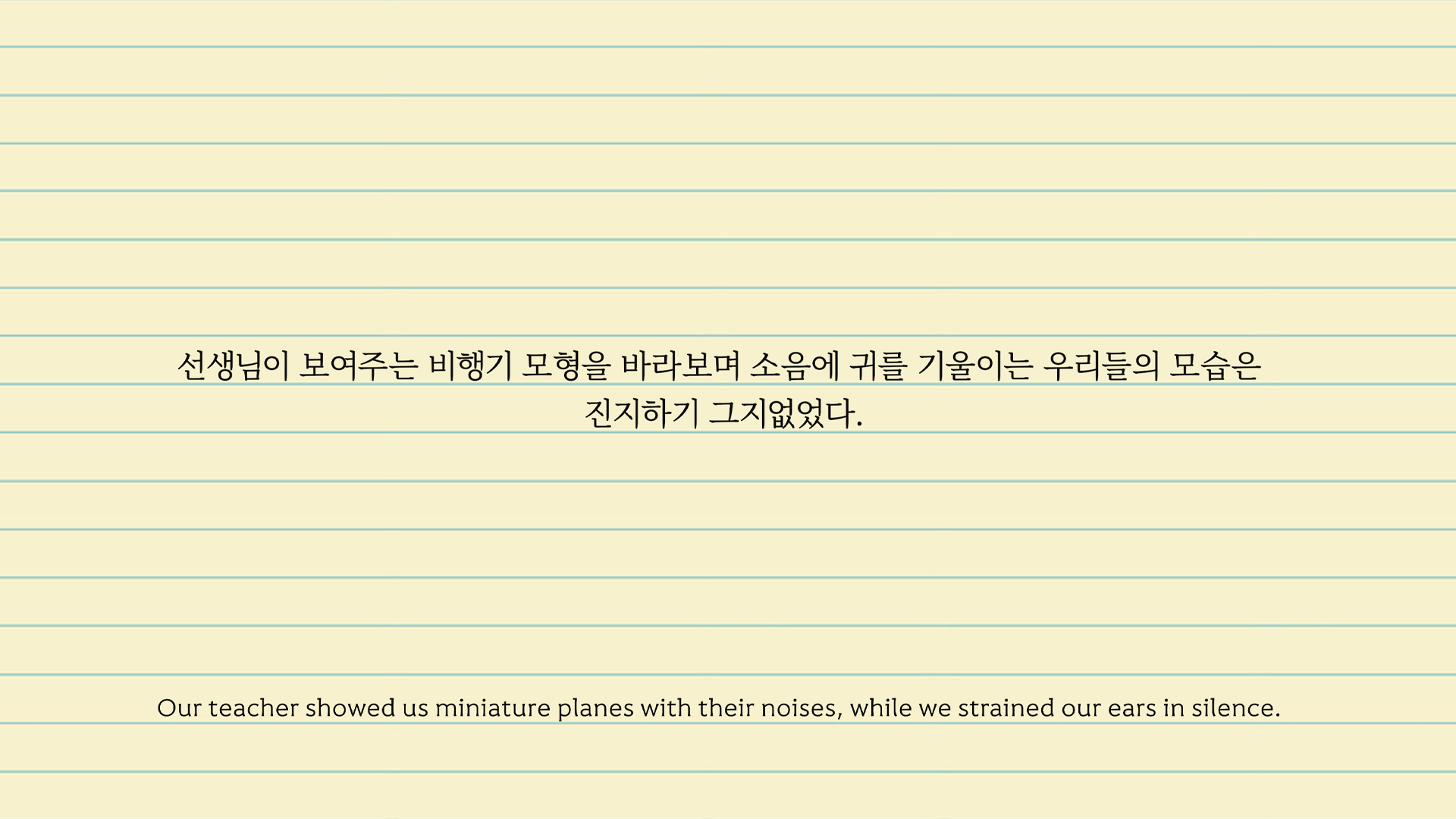

Ear Training

2022

Single-channel video, stereo & binaural sound

15 minutes

Ear training is an exercise aimed at identifying the pitch of a sound played on the piano, and it is a training that develops the ability to accurately perceive pitch, an element considered most important in Western music. As part of Western music education, this training evolved into a form of military training during the Sino-Japanese War, where soldiers honed their ability to identify the sounds of airplanes or detect submarine sounds. This adaptation was based on the logic that if one could internalize pitch through musical sounds, they could also recognize other sounds that correspond to the same pitch, such as the pitch of mechanical noises, even when their timbre differed.

This work reconstructs the ear training that took place in Japanese classrooms and military units during World War II. The ear training is reenacted by drawing on original scores written by students and soldiers who participated in the training, along with interview materials, archival recordings, and scholarly research on this period. The video includes the collection of sounds of enemy airplanes produced by the Army Anti-Aircraft School, underwater sounds analyzed by the Navy, and scenes of ear training tests, all presented from the perspective of a first-person narrator who recounts the auditory experiences of such. This work evokes the forgotten auditory world of a time when all things and senses subordinated to militaristic goals and when the “musical ear” was regarded as a form of munition.

(KR)

*This video features binaural audio recordings. For the best listening experience, listen with headphones.

2022

Single-channel video, stereo & binaural sound

15 minutes

Ear training is an exercise aimed at identifying the pitch of a sound played on the piano, and it is a training that develops the ability to accurately perceive pitch, an element considered most important in Western music. As part of Western music education, this training evolved into a form of military training during the Sino-Japanese War, where soldiers honed their ability to identify the sounds of airplanes or detect submarine sounds. This adaptation was based on the logic that if one could internalize pitch through musical sounds, they could also recognize other sounds that correspond to the same pitch, such as the pitch of mechanical noises, even when their timbre differed.

This work reconstructs the ear training that took place in Japanese classrooms and military units during World War II. The ear training is reenacted by drawing on original scores written by students and soldiers who participated in the training, along with interview materials, archival recordings, and scholarly research on this period. The video includes the collection of sounds of enemy airplanes produced by the Army Anti-Aircraft School, underwater sounds analyzed by the Navy, and scenes of ear training tests, all presented from the perspective of a first-person narrator who recounts the auditory experiences of such. This work evokes the forgotten auditory world of a time when all things and senses subordinated to militaristic goals and when the “musical ear” was regarded as a form of munition.

(KR)

*This video features binaural audio recordings. For the best listening experience, listen with headphones.

#1

Exhibition view of Korea Artist Prize (National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, Seoul, 2025). Image courtesy of National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea. Photo: Chulki Hong.

#2-3

Exhibition view of Frames of Sound (SONGEUN, Seoul, 2022). Photo: Jihyun Jung.

#4-5

Video still.

1 min video excerpt

Brilliant A

2022

Single-channel video, stereo or multi-channel sound

16 minutes 56 seconds

This work delves into the history of how the pitch “A,” used as the standard for tuning most modern instruments in orchestras and other musical contexts, became fixed at a frequency of 440 Hz. It also examines how the pitch has been set continually upwards over time, driven by human auditory preferences for “brighter” sounds. Apparent influences include the competition among instrument makers, who sought to capitalize on the demand for such sounds, as well as the practice of military bands in Europe and the United States, which aimed to send sound over long distances to boost troop’s morale. The work further reconstructs the speculative moment when the standard pitch A was introduced to Korea. The delivery process of a piano is recreated based on historical materials from the early 20th century, which document the arrival of the first piano in the city of Daegu, brought by an American missionary.

The introduction of the piano marked a pivotal shift in the theories and aesthetics of sound instilled in Koreans’ aural perceptions at the time, sparking a series of acoustic collisions that arose as the ear for traditional music gave way to the ear attuned to Western sounds. Through this reconstruction, the work explores the symbolic significance of the Western piano that brought the pitch “A” into Korean society.

Winner of the Korean Shorts Award at the 2023 Jecheon International Music & Film Festival

(KR)

2022

Single-channel video, stereo or multi-channel sound

16 minutes 56 seconds

This work delves into the history of how the pitch “A,” used as the standard for tuning most modern instruments in orchestras and other musical contexts, became fixed at a frequency of 440 Hz. It also examines how the pitch has been set continually upwards over time, driven by human auditory preferences for “brighter” sounds. Apparent influences include the competition among instrument makers, who sought to capitalize on the demand for such sounds, as well as the practice of military bands in Europe and the United States, which aimed to send sound over long distances to boost troop’s morale. The work further reconstructs the speculative moment when the standard pitch A was introduced to Korea. The delivery process of a piano is recreated based on historical materials from the early 20th century, which document the arrival of the first piano in the city of Daegu, brought by an American missionary.

The introduction of the piano marked a pivotal shift in the theories and aesthetics of sound instilled in Koreans’ aural perceptions at the time, sparking a series of acoustic collisions that arose as the ear for traditional music gave way to the ear attuned to Western sounds. Through this reconstruction, the work explores the symbolic significance of the Western piano that brought the pitch “A” into Korean society.

Winner of the Korean Shorts Award at the 2023 Jecheon International Music & Film Festival

(KR)

#1-3

Exhibition view of Frames of Sound (SONGEUN, Seoul, 2022). Photo: Jihyun Jung.

#4-8

Video still.

1 min video excerpt